Google alert failed to warn people of Turkey earthquake

Google’s earthquake warning system failed to get to many Turkish residents before February’s deadly tremor, a Newsnight investigation has found.

Google says its alert system can give users up to a minute’s notice on their phones before an earthquake hits.

It says its alert was sent to millions before the first, biggest quake.

However, the visited three cities in the earthquake zone, speaking to hundreds of people, and didn’t find anyone who had received a warning.

The system works on Android phones, essentially any phone that isn’t an iPhone. Android phones, which are often more affordable, make up about 80% of the phones in Turkey.

“If Google makes a promise, or makes an implicit promise, to deliver a service like earthquake early warning, then to me, it raises the stakes,” says Prof Harold Tobin, director of the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network.

“They have a responsibility to be able to follow through on something that is directly related to life and limb.”

Google’s product lead on the system, Micah Berman, insisted it had worked. “We are confident that this system fired and sent alerts,” he told the BBC.

However, the company did not provide evidence that these alerts were widely received.

More than 50,000 people died in February’s earthquake.

- Why was the earthquake so deadly?

After the first major 7.8-magnitude earthquake struck in the early hours of the morning, another major tremor shook the surrounding area at lunchtime.

The BBC was able to find a limited number of users who received a warning for this second quake.

How the system works

Google’s Android Earthquake Alert System was announced in Turkey in June 2021.

The system is operational in dozens of countries around the world. The company describes the ability to send quake alerts as a “core” part of its Android service.

It works by using Android’s vast network of phones. Smartphones contain tiny accelerometers that can detect shaking.

When many phones shake at the same time, Google can pinpoint the epicentre and estimate the strength of a quake. Google has made an explainer on how it works.

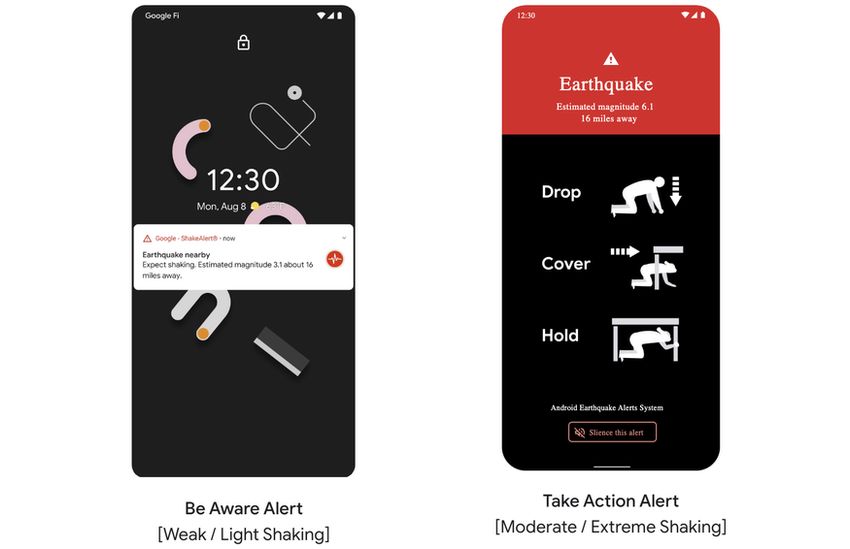

When an earthquake of magnitude 4.5 or greater is detected, the Android system can send a warning.

“This is an alert unlike any you’ve probably seen on your phone before. It takes over your phone screen,” Mr Berman says.

The warning says “drop, cover, hold” and is accompanied by a loud alarm.

It should also override a user’s do not disturb mode automatically, so you don’t need to switch it on.

“No matter what state your phone is in, you should get that warning,” Mr Berman says.

Google claims the system successfully sent alerts on 6 February to millions of people.

How much warning people should have got from Google would depend on how far away they were from the earthquake, Mr Berman explains. A message travelling over the internet can travel much faster than the waves of an earthquake travelling through the earth.

“Sometimes [the warning] might be a second or a fraction of a second, sometimes it might be 20 or 30 seconds, sometimes it might be 50 or 60 seconds,” he says.

Despite extensive reporting across the earthquake zone in the hours, days and weeks after the quake, no-one mentioned getting an alert to the BBC.

So we began to search specifically for people who had got the warning.

Our team travelled to Adana, Iskenderun and Osmaniye, cities between 70km (43 miles) and 150km (93 miles) away from the epicentre.

We spoke to hundreds of people with Android phones.

Although we managed to find a small number of people who had got an alert for the second earthquake, we couldn’t find anyone who got a warning ahead of the first, most powerful quake.

In Iskenderun, we spoke to Alican who lost his grandmother when a hospital collapsed. He says he had received the alert before, but he didn’t get it this time.

We put our reporting from the earthquake zone to Google’s Mr Berman.

He said: “It’s possible, given the massive impact of the first event, that this just quietly happened in the background, while users were really paying attention to lots of other things. At the end of the day, I think that’s probably the most likely explanation.”

But the people we spoke to were adamant that none arrived.

Funda, who has been living in a temporary tent encampment since the quake, says she lost 25 members of her family.

“We literally dumped people into the ground. My brother-in-law and nephew were buried hugging each other,” she says.

She owns an Android phone but told us she was “certain” she didn’t get an alert.

Quiet on social media

After an earthquake you would expect people to post on social media that they had received a warning. This is common in other countries where quakes have occurred since Google’s system launched.

“One of the few feedback sources that we have is being able to look on social media,” Mr Berman says.

And yet after the first earthquake in Turkey, social media was unusually quiet – something Mr Berman accepts.

“I don’t have a resounding answer for why we haven’t seen more reaction on social media to that particular event,” he says.

The BBC asked for data that showed people had received the notification. The only evidentiary document Google shared was a pdf with 13 social media posts the company had found of people talking of a warning that day.

So we contacted the authors of the posts.

One was Ridvan Gunturk, who had posted that he had got a warning in the city of Adana. However, after speaking to the BBC, he clarified that this was for the second earthquake. He confirmed he had not received an alert for the first earthquake.

In fact, only one of the social media posts referenced a warning about the first quake, giving a detailed account. The BBC has spoken to the author of the post, but they wouldn’t give their name.

The author said they believed they had received an alert, but couldn’t be completely certain of their memory of events at the time.

Google also said it had received feedback from user surveys that say the system worked. However, it declined to share this information.

Prof Tobin told the BBC Google’s system was relatively new, and could be useful, but that it was important for the company to be transparent.

“If you are delivering an essential life safety or public safety piece of information, then you have a responsibility to be transparent about how it works and how well it works,” he says.

“We’re not talking about an anecdote of, ‘oh it’s popped up here and there.’ These are intended as blanket warning systems. That’s the whole point.”

Turkish earthquake expert Prof Sukru Ersoy told the BBC his wife was in the earthquake zone. She has an Android phone but did not receive an alert.

He says that he has not spoken to anyone who got a warning.

“If Google’s system had worked, perhaps it could have been very beneficial,” he says.

“But the system not working in an important earthquake such as this one begs the question: if this is a beneficial system, why couldn’t we benefit from it in this major earthquake, one of the biggest earthquakes of the last 100 years?”

In a statement given to the BBC by Google after the interview, Mr Berman said: “During a devastating earthquake event, numerous factors can affect whether users receive, notice, or act on a supplemental alert – including the specific characteristics of the earthquake and the availability of internet connectivity.”