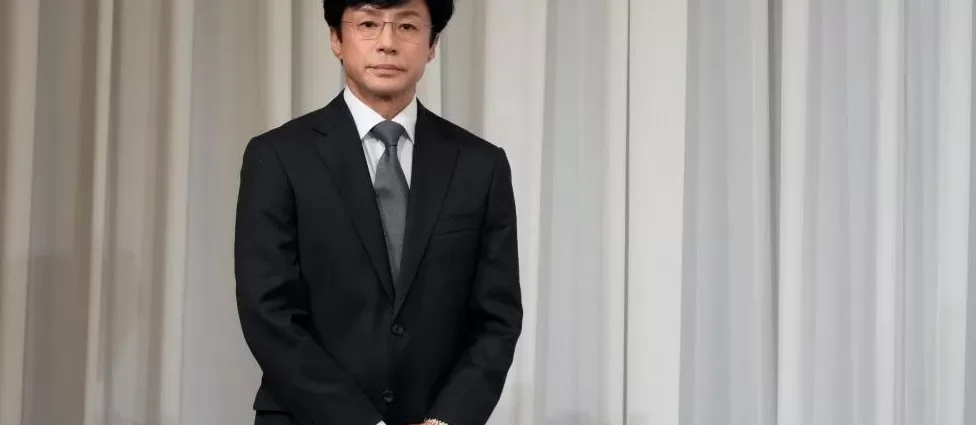

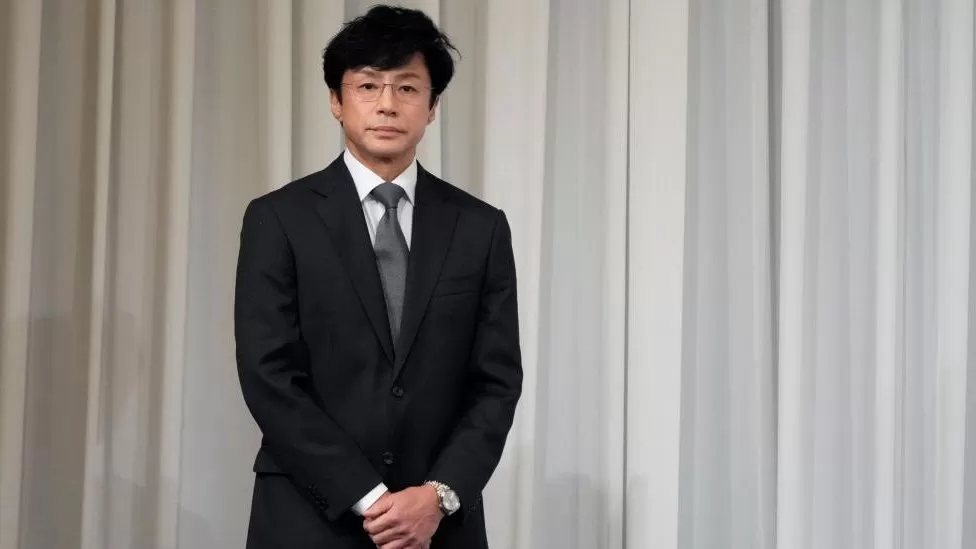

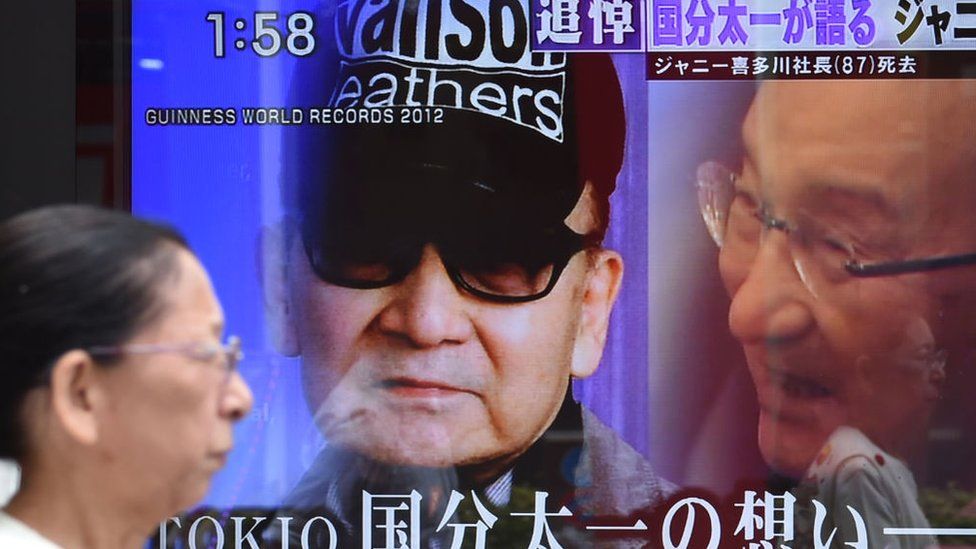

Johnny Kitagawa: J-pop agency’s new boss Higashiyama also faces abuse allegations

The new boss of a J-pop agency disgraced by the extensive sexual abuse committed by its late founder Johnny Kitagawa has also been accused of sexually assaulting young boys.

Noriyuki Higashiyama said he could not remember the reported acts which he said may or may not have occurred.

He was named the new boss of Johnny and Associates after Julie Fujishima resigned over her uncle’s offences.

He will lead the agency’s efforts to compensate victims and seek amends.

However, on Thursday at a press conference announcing Ms Fujishima’s departure and his appointment, he was also faced with questions about his own reported abuse.

Journalists asked him if allegations published in a book saying he massaged the crotches of boys, exposed his genitals and told them to “eat my sausage” were true.

He replied: “I don’t remember clearly. Maybe it happened, maybe it didn’t. I have trouble remembering.”

The 56-year old added it was possible that he had been stricter with younger performers, and that he may have done things as a teenager or in his 20s that he would not do now.

Mr Higashiyama, a household name in Japan, was one of the first talents recruited by Johnny and Associates. Online, many users have criticised his appointment, noting his long history with the company.

“It will take time to win back trust, and I am putting my life on the line for this effort,” he said.

He added that he had never been a victim of Kitagawa’s abuse but had been aware of the rumours.

“I couldn’t, and didn’t, do anything about it,” he admitted to the news conference.

Mr Higashiyama’s decades-old ties to the Johnny and Associates brand have also led many to question how he can change the company and, more crucially, protect its talent.

On Friday, Kauan Okamoto, one of Johnny’s victims who went public, broke down while speaking to the media, and said the person hurting the most is his mother.

“She has to live through it over and over and hear things that were done to me. There are things I can’t even say to her. I don’t want her to have to go through this ever again,” he said.

He also said he “respects” Mr Higashiyama and considers him “brave for taking this job that nobody wants”.

While Mr Okamoto said he hated Kitagawa for what he did, he is still “grateful to Johnny” for introducing him to the world of music.

“I know some would say this is grooming but this is how I feel,” he added.

Kitagawa was arguably the most influential and powerful figure in Japan’s entertainment industry. His agency has for decades been synonymous with J-pop culture, and was the gateway to stardom for many young men.

But Johnny and Associates now bears the name of a sexual predator.

At Thursday’s press conference, when asked if there were plans to change the company’s name, Mr Higashiyama said there were none.

On social media, a user questioned how he would be able to “rebuild the agency when everyone will be looking at you with coloured lenses?”

“Is this the end for the company?” the user added.

Last week, an independent inquiry found the pop mogul abused hundreds of boys and young men over six decades, including while head of the boyband agency.

He died at 87 in 2019, having never faced charges and always denying wrongdoing. Kitagawa’s death was a national event – with even the then prime minister sending condolences.

Although reports of his abuse were an open secret in the industry, for decades mainstream Japanese media did not cover the allegations.

But a BBC documentary this year about Kitagawa and the J-pop industry sparked national discussion and prompted more victims to come forward. It led to the independent investigation, which last week recommended that the agency’s boss resign.

Outgoing chief executive Ms Fujishima acknowledged Kitagawa’s abuse for the first time on Thursday.

She said the pop mogul had been so powerful that many in the agency, including herself, kept silent.

The company also has considerable power over many media outlets, said Matsutani Soichiro, a journalist who has covered the Japanese entertainment industry for years.

He told local media in May that declining revenue for TV stations and magazines have made them overly dependent on Johnny and Associates’ idols for ratings.

In 2019, for example, a Japanese regulator issued a warning to Johnny and Associates after it found that the agency had pressured TV stations not to showcase idols who had left the company.

Mr Soichiro added that unless the root of the problem is addressed, similar things could happen at other talent agencies.